QMAC electronics was an Australian firm who produced affordable portable and mobile HF radio equipment. Their target market was aid agencies, NGOs, scientific expeditions, and military/paramilitary organizations. Their core product was the QMAC HF-90. Remarkably small for it’s time, the HF-90 boasted up to 50W of transmit power, frequency hopping, and easy field serviceability.

One of products in the QMAC catalog was an interesting terminated end-fed antenna, model QM7005. The antenna is considered terminated because of a load resistor installed in series along the transmitting element. It is an end-fed because it uses an unbalanced-to-unbalanced transformer (UNUN) to feed a long wire against a short ground or counterpoise wire. This antenna was marketed for HF manpack use or as emergency antenna for mobile operations.

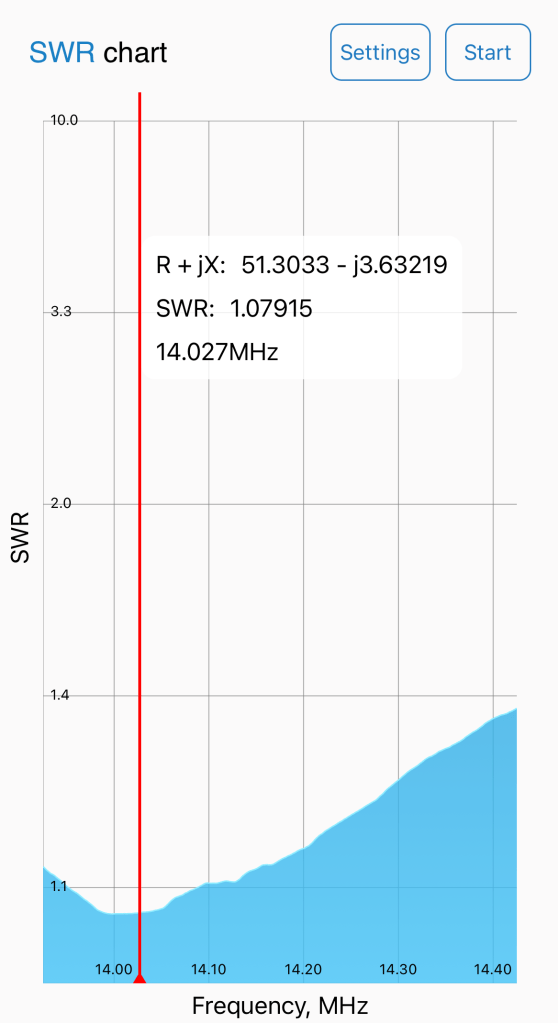

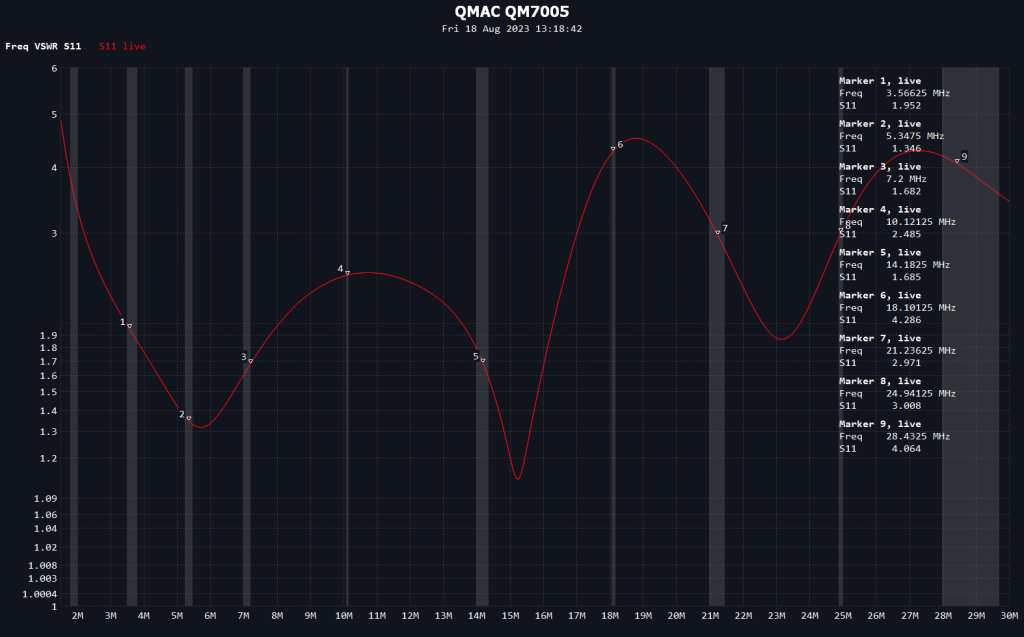

The terminating load on this antenna is intended to deliver broadband coverage with acceptably low SWR from 2-30 Mhz. The HF-90 could handle SWR up to 3:1 and later models had significant built in protection for the RF final amplifier.

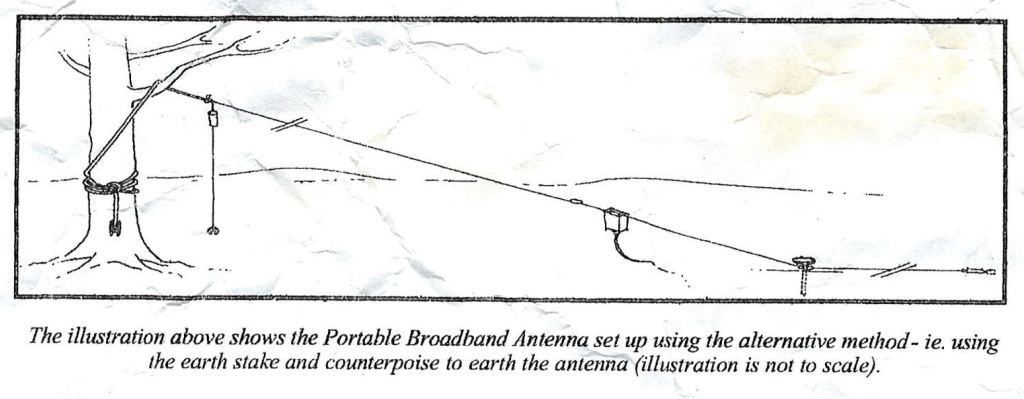

The included instructions recommend two deployment variations. The preferred method is to use a vehicle as tie off and grounding point. Alternatively, one may deploy the antenna counterpoise along the ground.

Ordinarily, I don’t drive a vehicle out to the areas I operate in so I decided to test the antenna using the alternate method pictured above. All the guy points needed to achieve this deployment come integrated into the antenna. Below is the NanoVNA sweep of the antenna from 1.5-30 Mhz.

The QM7005 kept VSWR below 3:1 from about 2 Mhz up to about 17 Mhz. Above that point results varied significantly by frequency. For most purposes where this antenna and radioset would have been deployed, namely local and regional communication, this performance would have been sufficient. The most consistent performance for an antenna like this occurs on the NVIS frequencies anyhow as the radiating pattern of the higher bands ceases to be omni-direction and instead breaks ups into an increasing number of lobes and nulls.

In case someone would like to build or experiment with this type of antenna, I went ahead and reverse engineered it.

Moving from left to right on the diagram starting with the ground connector, a simple spring loaded alligator ground clip is used. The UNUN in my sample was wrapped with tape and sealant so I couldn’t discern the winding pattern without risking destroying it. Using a 450ohm resistive load, however, I was able to confirm it was a 9:1 ratio. The design used by QMAC was not as broadband as it could be if it used a different core or winding pattern. If you decide to build your own, I recommend using a FT140-43 toroid from Fair-rite as these give good broadband performance well above 30 Mhz. Lastly, the terminating load is a 1.1k ohm resistor. Again, I wasn’t able to disassemble the load for inspection but any non-inductive power resistor from Ohmite should work for this application.

While in the field, I used this antenna to check Winlink email and had no difficulty connecting to my usual gateways within NVIS range.

For your reference, I’ve also scanned a copy of the QM7005 Instruction Manual.

Padre