TL;DR: Motorola DTR 900Mhz FHSS radios perform at least as well as other popular radios operating on FRS, GMRS, or MURS. Additionally, they add a level of privacy that can’t be matched by any other license free service and, by some measures, offer security better than encrypted radios operating on a single frequency.

INTRODUCTION

Frequency Hopping Spread Spectrum (FHSS) is a technique used in radio communications. In an FHSS system, a transmitter changes frequency on some schedule (usually many times per second). Contrast this with single-channel radios which may be able to change frequencies but can only transmit or receive on one frequency at a time. For an FHSS system to work, the receiver must be synchronized with the transmitter in some way and both the transmitter and receiver must have prior knowledge of the frequency hopping sequence to use so they can remain synced.

Historically, FHSS has been complex and expensive to implement. Additionally, the FCC prohibits use of FHSS in the amateur radio service below the 70cm band. This has kept the use of FHSS by experimenters to a minimum, thus relegating it to government agencies. There is, therefore, a dearth of readily available equipment to put FHSS to practical use. That is a shame because FHSS offers a number of advantages that are worth listing here.

- FHSS systems are resistant to radio interference, multi-path attenuation, and jamming. Obviously this feature has military applications but with the proliferation of interference causing devices it is also a feature for the informed operator. It also means better performance at the edge of coverage or from mobile stations than single-channel radios.

- FHSS systems are more efficient users of radio spectrum. Single-channel radio services require strict frequency assignments and channel spacing to avoid interference. Users who are assigned a frequency occupy that spectrum whether they are transmitting or not. FHSS, like trunking LMR systems, allows more users to share the frequency spectrum. A great feature for crowded spectrum conditions.

- FHSS systems are harder to detect and direction find than single-channel radios. No consumer grade scanners are fast enough to detect and track FHSS signals. Similarly, you won’t hear them on a conventional receiver. The signals can be detected by a spectrum analyzer, SDR, or possibly a near-field receiver, but can’t be eavesdropped on with any of the above. This means FHSS offers significant privacy advantages even without encryption.

ENTER THE DTR650

I have been aware of Motorola’s DTR series radios for at least a decade as they are actually old technology now. Based on the iDen cell phones that were used by Nextel for their DirectTalk (that quirky walkie talkie style operation between cell phones you remember from the 90s) feature, the DTR series radios have been out since the early aughts. They were close to $400 per handset at time of their release and prices stayed high for a long time, keeping me out of the market. A couple of years ago, Motorola released their second generation DTR lineup so legacy users are now upgrading their fleets. Lots of DTRs are hitting the surplus market so now is a good time to look on eBay for a good deal. That is how I ended up getting a lot of five DTR650s for 60 bucks a pop, complete with batteries and chargers. As with everything on eBay, caveat emptor. Make sure all the parts are included for a working radio if decide to bid.

Although classed as business radios, the Motorola DTR series operate in the license free 900Mhz ISM band. As such, they are limited to one watt of output power (not a major limitation for simplex use).

The DTR650 is the top of line radio in what I would call the “GEN 1” DTR line-up. The other radios in this generation are the DTR410 and DTR550. They look like late 90s era cell phones and share some accessories with the iDen phone lineup. I can confirm, for instance, that the iDen car charger works with the DTR650s.

With a little TLC, my small fleet of DTR650s cleaned up nicely. The screens are bit scratched but it doesn’t affect function so I’m not going to worry about it. It seems spare parts are still available from various Motorola dealers and on eBay if you need something.

Unlike most Motorola products, the Customer Programming Software (CPS) for these is a free download. Just do a search for Motorola Business Radio CPS. You don’t the CPS to program most functions as an exotic series of key presses will put the radio into programming mode. That said, I highly recommend getting a programming cable and using the CPS if you are going to work on more than a couple of these radios. If you have programmed other business band radios before, like DMR or P25 type radios, then you’ll pick up how to program the DTRs in a just a few minutes. If you’ve never programmed a part 90 radio before then the next section should help clarify how these work.

PROGRAMMING THE DTR650

Each DTR handset has a unique serial number assigned to it. The CPS can read this number back automatically to save you some time. The programming file you will create for these radios, called a codeplug, needs to include the serial numbers of all the other radios in your network if you want the private talkgroup or private one-to-one features to work. So the first step is to read back all your serial numbers into the CPS. I then copied these to a spreadsheet for future reference.

In the CPS, you’ll enter your serial numbers as “Privates” in the appropriate field. You can also give your radios a unique human readable name.

There are ten available “Channels” but these aren’t channelized frequencies in the traditional sense. Instead, each DTR channel is a set of 50 frequencies between 902 and 928 Mhz called a hopset. The DTR family of radios hops frequencies at a rate of 11 times per second for a dwell time on any particular frequency of about 90ms (yep, that’s milliseconds). You can segregate traffic on your network by using the ten channels but you can also setup multiple talkgroups to use the same channel because the radios will only respond to other radios using the same talkgroup. In fact, the radios come configured from the factory with five talkgroups pre-loaded and all of these use channel 1.

When you setup your Privates in the CPS, you have to assign a channel to the radio. I’m not sure why they forced this on the user, because the radios can operate between channels using public talkgroups. To use the private talkgroup feature, however, you can only use the channel assigned to the radio. With the DTR650s this means you can only effectively have one private talkgroup. This is true because even though the radio allows you to create multiple private talkgroups, the DTR650 (and presumably others in the series) always scans all the private talkgroups and responds to any that are transmitting. So there really isn’t a way to segregate traffic on your radios using multiple private talkgroups. I find this to be an odd limitation but I’ll admit you can configure public talkgroups to have substantial privacy by changing the defaults so this probably isn’t a practical limitation for most networks.

PRIVACY & SECURITY

Public talkgroups will allow any handset using the same channel and talkgroup name to communicate with the network. The DTR650s come preprogrammed with five public talkgroups already setup. A number of DTR users have noted that business users of these radios often use the default public talkgroups so are easy to eavesdrop on.

Private talkgroups increase the level of security by restricting the talkgroup to handsets that know the private ID of the talkgroup. The CPS asks you to choose one of the serial numbers in the talkgroup to be the private ID. This is a potential security risk because the handsets broadcast their ID on the public talkgroups which could allow someone to collect the private ID of your private talkgroup. Not a problem though, because you can create a Private with a bogus serial number you make up and add it to your codeplug. That bogus ID won’t ever transmit on a public talkgroup so you can use it as the private ID of your private talkgroup without concern that another user might exploit it.

Initially, I assumed that this private talkgroup feature was like a selective digital squelch that would open only for those radios listed as belonging to the private talkgroup. That isn’t the case though. Any handset that has the correct private ID can communicate with the private talkgroup whether a particular handset lists the transmitter as a member of the talkgroup or not.

There was some speculation some time ago that the private ID of the private talkgroup was a seed used to randomize the hopset. If true this would offer substantial additional security. Sadly, I don’t have the equipment or expertise to validate this. That said, I have my doubts that these radios are that sophisticated. More likely, each hopset has a set pattern that is always used with metadata such as the handset ID, talkgroup ID, or private ID being used to segregate traffic. Even if Motorola’s algorithm had a mechanism for randomizing the hopset, they must be using a synchronization frame at the beginning of each transmission because the alternative would be having very accurate Time of Day (TOD) clocks on each handset. This would drive up both price and user frustration as even small differences in clock synchronization would cause missed transmissions. In any event, the synchronization frame by definition must contain enough data for the other handsets in the network to receive the transmission. This being the case, hopset randomization would only increase security in the event that an eavesdropper couldn’t receive or decode the synchronization signal.

While you might rightly conclude that the Motorola’s FHSS implementation is fairly simple it would be wrong to conclude that it offers no security. As I write this, there is no off the shelf solution to listen in to these radios. No consumer level scanner or communications receiver will do so. These are even safe from currently available SDR dongles and decoder software. My SDR with the widest receive bandwidth is the HackRF One which is capable of staring at 20Mhz of spectrum at once. This still isn’t sufficient to capture the full 26Mhz frequency hopping range of the DTRs. It might be possible to use several cheap RTLSDRs in parallel if you knew the hopping pattern and could tune the dongles fast enough to follow the hop rate. There are libraries available to decode the VSELP vocoder used by these radios to digitize voices, assuming Motorola is using a standard VSELP implementation. Since its Motorola we’re talking about here, of course it’s proprietary! So there would almost certainly be some additional reverse engineering and software writing required to build a solution for monitoring these. If I had to guess, a college student could probably get a working prototype underway with 3-6 months of development using COTS hardware and a combination of open source and custom code. Being a niche product, nobody to date has put in the work on this.

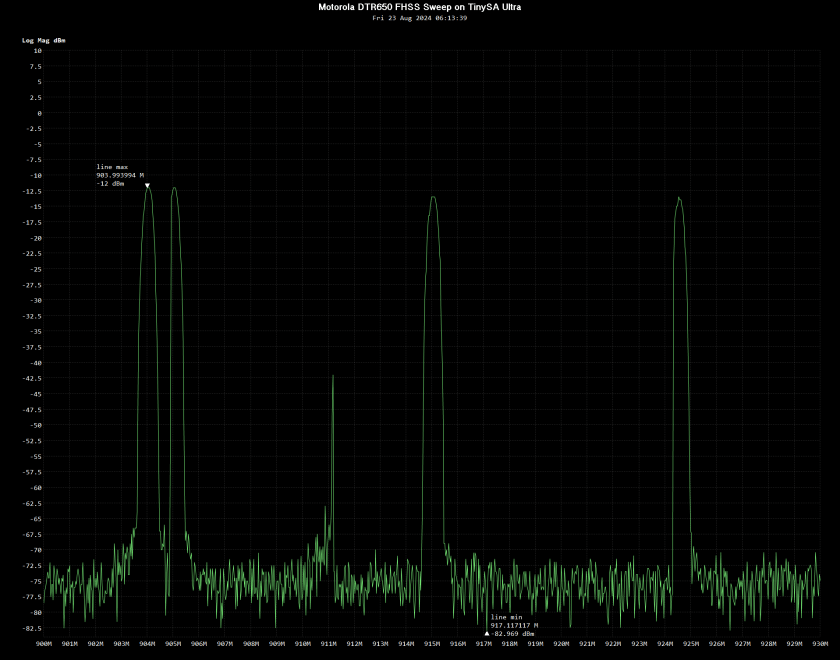

So you can’t eavesdrop on these radios but can they be detected? Yes, they can. A spectrum analyzer or SDR dongle will at least do that. My TinySA Ultra doesn’t refresh fast enough to fully track the hop pattern but easily detects enough signals in the 900Mhz ISM band to make it obvious to a trained user that FHSS is being used. In crowded urban conditions, however, the DTR traffic might blend in with other 900Mhz traffic from consumer devices, hospitals, and SCADA systems, especially since these are limited to 1 watt of output power. I also tested the Close Call feature on an SDS100 scanner. The SDS100 will show you there is activity in the UHF band but doesn’t give a close call hit. Some folks have said a near field receiver like the Optoelectronics Xplorer will detect and follow the hopping pattern on DTRs but I wasn’t able to replicate that result myself.

In sum, these DTRs offer significantly more security that any other consumer level radio. Encrypted radios might offer more privacy but the only commercially available encrypted radios are single-channel solutions like P25 or DMR. Off the shelf scanners will detect P25, DMR, NXDN as well as analog using basic frequency searches as well as by using features like Uniden’s Close Call. Even if I can’t listen in on encrypted P25 traffic, for instance, I can certainly know that it is there and knowing someone is there is useful all by itself. I can also use off the shelf tools to do traffic analysis on P25 or DMR networks even if they are encrypted because the metadata is not. There is no comparable way to exploit DTRs using off the shelf tools, either to monitor the transmissions or the metadata.

Put another way, we can distinguish between Communications Security (COMSEC) and Transmission Security (TRANSEC). Encrypted P25 radios, for instance, offer COMSEC because they protect the contents of each transmission from anyone who doesn’t have the appropriate key. The Motorola DTRs, on the other hand, offer TRANSEC because they obscure the fact a transmission is being made at all and make it extremely difficult to monitor even if the signal is detected. It may be a form of security by obscurity but if you know that and it fits your use case then you may get a lot of value from the DTRs.

PRACTICAL USE IN THE FIELD

The first thing everyone asks about two way radios is, “How far can I talk with these things?” Range in my mixed rural/residential neighborhood was about a mile. Comparable to other other simplex services like MURS or GMRS. Frankly, I was impressed because the summer foliage in my AO is almost jungle thick and I expected significant performance issues on 900Mhz in this environment. Others have posted ranges of 10-20 miles in open terrain such as along coastlines or in the desert. Like other VHF/UHF radios, these are terrain limited and not propagation limited. Motorola advertised these as ideal for urban use in office buildings and warehouses. In those environments, you can probably expect outstanding performance as 900Mhz penetrates urban construction well. Several online users have noted these radios as working especially well on cruise ships with better deck penetration than GMRS.

There is a slight learning curve to using the DTRs as they are fully digital radios. Users used to analog radios will be a bit annoyed at first because there is a slight delay between pressing the PTT and being able to talk. To start a conversation, push the PTT and wait for the talk-permit tone, then start speaking. If you don’t wait for the talk-permit tone, the start of your conversation will get cutoff. This is consistent with other digital radios, even professional P25 and DMR radios, especially if they are on trunking systems. Users accustomed to digital shouldn’t have a problem. I was able to teach both my wife and my elementary aged kids how to use these radios with just a few minutes of instruction.

An interesting feature of the DTRs is that they will let you know if there are no users within range on your talkgroup. This makes range testing easy as you won’t need a partner to help you. It also keeps you informed if your group gets too spread out of if intervening terrain or structures are blocking your signal.

Given their cell phone lineage, the handsets are rather lightweight. Battery life is excellent and should last at least one normal work shift, possibly two, before needing to be recharged. My batteries are all at least a few years old and still giving decent service.

The DTR650s use rubber overmolded plastic construction and sport a MIL-STD 810 compliance rating. They are substantially more rugged than a Baofeng but not up to the standard of submersible radios like the Yaesu VX-6R or professional public service radios like Motorola’s XTS or APX series. Overall I like the construction of the DTR650s, they have character and are a nostalgic reminder of the 90s.

Sadly, the rubber overmolding on a lot of these is showing its age and is getting brittle. Heavily used Gen 1 DTRs often show signs of the rubber disintegrating. Port covers built into the overmolding frequently break off their hinges. For casual use it shouldn’t be a problem but demanding users will want to consider getting the current generation DTR600 or DTR700 radios.

The antennas on these are removable and Motorola offered at least two antenna variants, a quarter-wave stubby and a longer half-wavelength model. Spare antennas are getting harder to find so I haven’t yet acquired a pair of the longer antennas to do comparison testing. The stubby antennas seemed to have been the most popular judging from the used radios available on eBay. Larger external antennas, including homebrew, should be possible. Other folks who have published their results said they didn’t work but I expect that is because Motorola uses a semi-proprietary SMA connector on their handhelds. It is called an SF SMA and RF Parts has SF SMA to BNC adapters available. I acquired a couple of these adapters and early testing looks promising. Of course, the attenuation over coax of any 900Mhz signal is going to be high so long cable runs will quickly negate any gain advantages of a larger external antenna. Keep the cable runs short!

A feature noticeably missing from these radios is a feature to lock the keypad. On part 90 programmable radios I enable the keypad lock by default so inadvertent button presses don’t cause issues. Lacking this feature, the DTRs are definitely susceptible to ending up on the wrong talkgroup if the user accidently presses the wrong button. There is a partial mitigation for this. In the CPS, under Privates, set the handset Homegroup to the talkgroup you want to use. With this setting in place, the user can change the talkgroup only temporarily. After 30 seconds of inactivity the handset will revert to the Homegroup. Handy to keep everyone on the same talkgroup but a pain if you have a large fleet of radios and need to make decisions on how to segregate traffic in the field.

There is one firm offering a repeater compatible with the Motorola DTRs. It is expensive at around $1,500 per device and each repeater system requires two of these devices. These repeaters are also limited to the 1 watt maximum power allowed by the FCC for FHSS devices on the 900Mhz ISM band so don’t expect miracles.

A BRIEF NOTE ON THE FUTURE

At the time of this writing, there is a proposal from a business entity before the FCC to commercialize the 900Mhz ISM band used by the DTRs, as well as cordless phones, baby monitors, Meshtastic nodes, and innumerable other devices that rely on low power, license free spectrum. It is unclear if these millions of legacy devices will be grandfathered in if the FCC approves this request or if the devices will even be useable if they are. The company forwarding this proposal wants to operate 2kw transmitters on a portion of this band. I can’t imagine many devices handling that level of interference gracefully. Keep an eye on this proposal and reach out to the FCC with your comments if this sounds troubling to you.

CONCLUSION

The Motorola DTRs have a number of significant advantages and few faults. I suspect most users of GMRS or MURS would be better off with something like these unless they truly need the coverage offered by a GMRS repeater. The only real disadvantage to these I can think of is a lack of interoperability with other radio services. These aren’t general purpose, one-size fits all radios. Rather, if you want simple, high privacy, and high reliability communications for on-site applications then consider trying these, especially if you might be operating where GMRS or MURS congestion is high. Properly programmed, you’ll never hear another soul on these you don’t want to hear and they won’t hear you either.